Background

What can I say? Happy Hour had been long and exuberant, and now 07:00 hours Saturday April 1, 1972 my squadron, the Black Panthers (35th Tactical Fighter Squadron), and its F-4Ds were on the move from Kunsan airbase Korea to South East Asia (SEA). TDY to Vietnam. (YES! Recall was on APRIL FOOL’S DAY! It was NOT pretty. But, that’s a whole ‘nuther’ story!). It was just the beginning. May 1972, hardly unpacked, we left the 366th TFWing at DaNang to join the 388th TFW at the Royal Thai Air Force base at Korat, Thailand.

The 35th was one of the most experienced F-4 squadrons in South East Asia (SEA). Although we had about 8 1Lt aircraft commanders, we had been training them for 6 months prior to deployment. The rest of the squadron averaged over 1800 hours of F-4 time and included 8 Fighter Weapons School graduates (Commanding Officer Lieutenant Colonel Lyle Beckers, Major Walt Bohan, and Captains Charlie Cox, Jim Beatty, Joe Moran, George Lippemeier, Will Mincey, and me).

0600 Hours, 20 July 1972

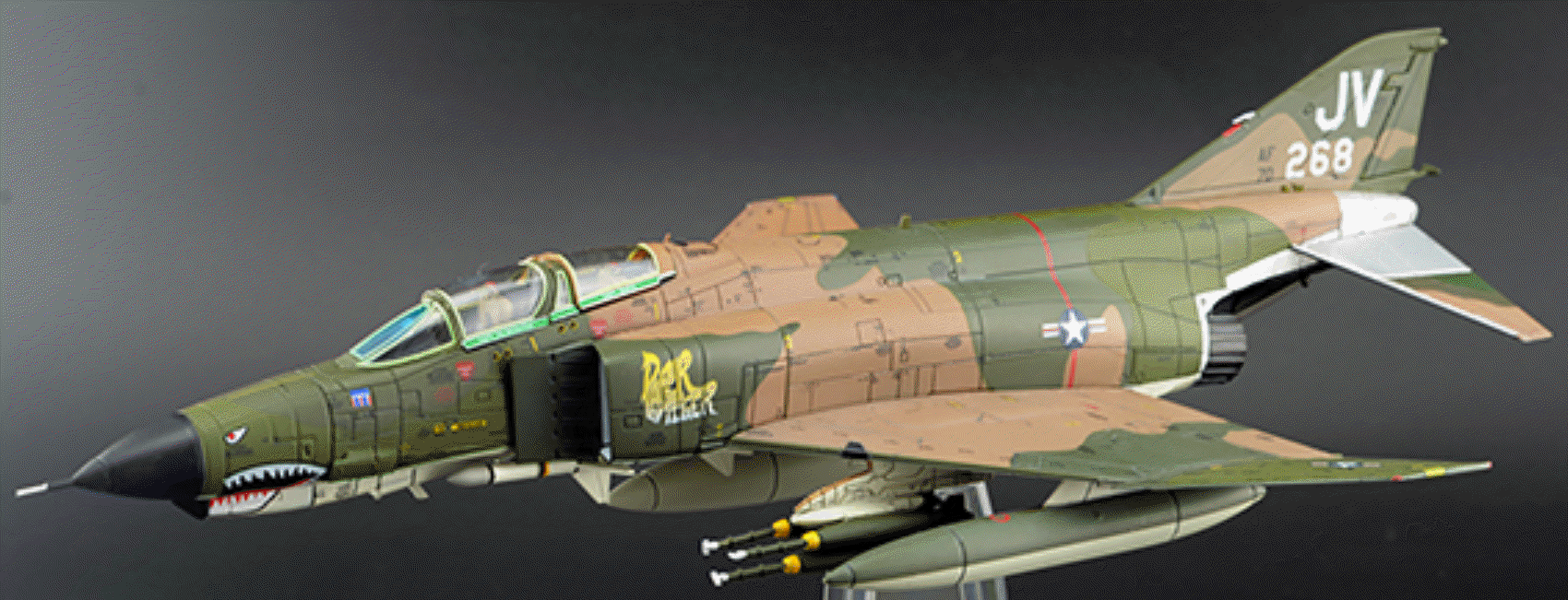

We are being briefed on a mission to Route Package 6; bombing the underground fuel storage area located about 12 nautical miles southeast of Hanoi. Our mission is a mini- strike package with 16 of our F-4Ds acting as “iron haulers”. That is, eight ships ((call signs “Caddy”(1st Striker) and “Buick” (3rd Striker)) each carrying 12 iron bombs (500 pound Mark 82) with delay fuzzes. An additional eight ships ((2nd Striker (“Dodge”) and 4th Striker (“Chevy”)) would be each be carrying 9 incendiary mix CBU 58s.

The ‘plan’ calls for Caddy and Buick flights to break open the earthen revetments with their 500 pounders and Dodge and Chevy flights to ignite the exposed fuel. Our MIG cover would be provided by eight F-4Es (“Pistol” and “Saber” flights) armed with Sparrow (radar guided) and Sidewinder (heat seeking) missiles, plus the internal 20mm Gatling gun. Each of the F-4s carried a radar jamming pod. All the aircraft and spares would be flying out of Korat. Support missions would include the mix of Wild Weasels, tankers and Command and Control aircraft.

Weather is reported to be scattered clouds in the target area, with a scattered to broken cloud deck to the east along our exit route toward the North Vietnam coast “feet wet”. Intelligence warns us about a potential ‘new’ Surface-to-Air (SAM) missile site just north of Thud/Phantom ridge, roughly half way between Hanoi and the coast line to the east.

After ‘wheels-up’ the 24 ship strike force and spares are to join up and proceed to `Purple’ Tanker orbit abeam of the city of Vinh out over the Gulf of Tonkin. After mid-air refueling we would cross the North Vietnam coast (`feet dry’) North East of Thanh Hoa. Our Initiation Point would be Minh Binh and from there to the target. After the strike we would egress NE then east just North of Thud/Phantom Ridge to feet wet, then South to Purple tankers and RTB (Return To Base – for us, back to Korat).

The Mission Commander, Caddy 1, is Major Walt Bohan and I, Caddy 3, am the Deputy Mission Commander.

The rest of the mission briefing is ‘normal – normal’. Well, except for this. Sometime during the mission brief, out of the corner of my eye, I notice that “Roscoe”, the Korat fighter pilot dog-warrior-mascot gets up and leaves the briefing room. “Aw, heck”, says me. That’s just a superstition, isn’t it? It probably doesn’t really mean this will be a “tough” mission (i.e., lose an aircraft). Heck, sometimes a dog just has to take a whiz!

All 24 aircrews and spares ‘step’ at 9:15 for a 10:30 takeoff.

(Now here’s where the hair on the back of your neck should start bristling – as in: “oh oh”, things aren’t going “as briefed”!! I know MINE did!)

Shortly after engine start Caddy 4 ground aborts Air Refueling Door Failure), dashes to a ground spare, but it ground aborts also. A ground spare replaces Caddy 4. (Capt. Jim Beatty in F-4D with 500 pounders, who had attended the Caddy flight briefing.) Taxi as 4 ship. At EOR (End Of Runway checkpoint) Caddy 2 ground aborts for a massive hydraulic leak. Caddy Flight takes off on time as a flight of three with the rest of the strike force in tow.

(Did I ever tell you about Jim Beatty’s ‘world renown’ May ’72 supersonic Mig-21 gun kill while flying an F-4E out of DaNang. Supersonic? Yep! He and his pitter had pretty sore necks as their F-4E went through ‘mach tuck’ and hit jet wash just as the Mig burst into flames!! Pegged the G meter!! The jet was down for a few days, too! )

Rendezvous with tankers in Purple orbit uneventful – gas passed in reverse order (i.e. – 4, then 3, then 1) per briefing – except for Caddy 1 who keeps getting disconnected. He backs out so Caddy 3 and 4 can top off and then tries again. At about this time, an air spare joins Caddy flight. It’s an F-4E with CBUs from the 421st TFS, flown by Captain Sammy Small. He tops off after Caddy 4. Caddy 1 can’t get his Flight Control Augmentation System (CAS) to stay on line, is VERY sensitive in the pitch axis and can’t take any more gas. He aborts, making Caddy 3 the mission commander.

(I’ve never been on a mission with this much ‘trouble’ BEFORE we even get to the target!!)

Due to armament, flight call signs are rearranged. Caddy check in is “Caddy 3 check”, “2” (Jim Beatty F-4D with bombs), 4″ (Capt. Sammy Small F-4E with CBUs).

(I am often questioned about proceeding with the mission as a 3 ship. Best I can remember there was a Wing policy that covered going on a mission with less than the fragged number of aircraft, armament different from fragged, etc. However, comma, the original Caddy 1 seemed to have been going to target with 3 jets; we had 12 ‘bombers’ and 8 ‘escorts’ right behind us; AND the target dictated delayed fused bombs to expose the POL followed by CBUs to assure the POL caught fire. “That’s my story, and I’m sticking to it!”)

After drop-off from tankers, ingress proceeds as briefed: feet dry NE of Thanh Hoa, IP (Initial Point) at Ninh Binh to target. Slight weaving along route at an altitude of 18,000 to 22,000 feet.

(Another bad sign! When the flight switches ‘Master Arm On’, one of Caddy 2’s bombs just sorta falls off its rail! Cripes! Hope it doesn’t hit those Navy ships!!)

In bound route is eerily quiet. My ‘pitter’ Lieutenant Mike Nelson and I discuss target area responsibilities again. There is very little activity on the Radar Homing and Warning System (RHAW); only occasional, short beeps from various enemy radars (Ground Control Intercept (GCI), Fansong SAM (Surface-to Air Missile), and the larger Anti – Aircraft Artillery (AAA) tracking radars).

The ‘new’ Caddy 4, rightfully, since he was not in Caddy’s briefing, asks from which direction was roll in and moves to right combat echelon as we approach the target area.

I can see the target area is almost free of clouds – some scattered ones at 8 to 10,000 feet – a heavier, layered deck appears to cover the egress route.

For an underground fuel storage site, this one is fairly easy to identify from altitude due to good intelligence target photos of the dirt roads. As Caddy flight approaches the roll in point, a single 85-mm AAA gun starts shooting in the vicinity of the target area – dense black flak balls widely scattered at 15 to 18,000 feet. It’s 1145 hours.

“Caddy, check switches hot – Caddy has target in sight – Lead’s in.”

Ground level winds in the target area were forecast from the NE and it looks about right to me from the movement of low clouds and smoke from ground fire. Briefed aim point for Caddy’s bombs and Dodge’s CBUs was the SW half of the target area, so that Buick and Chevy flights could target the NE half of the target area without being hindered by smoke from Caddy and Dodge’s ordinance (and, hopefully, secondary explosions).

Caddy 1 is thundering ‘down the chute’ at 500+ miles per hour in a 60-degree dive. I stop the wind drift with the ‘pipper’ (aiming device) directly on the target and ‘pickle’ off my deadly weapons at 14,000 feet. (Funny how the ‘light, sporadic 85 mm flak seems MUCH heavier during the pass!!) All bombs off, I start a hard 6 ‘G’ pull, jink left, and then jink hard right as we bottom out about 7000 feet. I continue in a hard right turn climbing toward 10,000 feet and heading for the north side of Thud/Phantom Ridge.

Coming off target, Mike and I crane our necks against the G forces scanning the ground and skies for SAMs, AAA and Migs. I notice several 37 or 57 mm AAA guns joining in the defense of the target area – but still only at the ‘moderate’ level. As I look back over my right shoulder, I see my two wingmen below and inside my turn – no immediate threat to them or us, says my fearless pitter, 1/Lt Mike Nelson. As the join up to combat spread formation ensues, I get a look at the target area some 10 – 15 miles away. Black, heavy smoke, with fires visible at the ground, rising to some 18,000 feet as the second wave’s ordinance starts to impact. (Sierra Hotel!! We won’t have to come back to bomb THIS fuel dump for a while!!)

(That feeling of knowing that the bombs are on target is wonderful. The fact is our bombs didn’t always hit the target, or that if they hit the target, the ‘target’ really wasn’t there anymore – i.e., no secondary explosions. So far on THIS mission, it appeared the mission objective is accomplished and things look pretty good!)

As Caddy 2 and 4 join to combat spread (I’d been turning enough in a high-speed climb to give them cutoff), we see the thickening cloud deck to the East from 5 to 12,000 feet. This observation, plus the intelligence briefing on a possible new SAM (Surface-to Air Missile) site, makes me decide to drop down and egress at 500 feet Above Ground Level (AGL).

(YES, the thought also crosses my mind that a few MIGs might be lurking at low altitude to snipe at us along our egress route. Specially since I had just been on our Wing DCO’s wing the day before when he went out north of Thud/Phantom Ridge at low altitude!! Mike was busy fine tuning the radar in search of low altitude ‘bogies’.)

I hear a little UHF radio chatter as the following flights come off target, rejoin and start their egress. It sounds like we got lots of bombs on target with good secondary explosions and big fires. Not much activity on the RHAW scopes, but there is a SAM (Surface-to Air Missile) radar warning call from one of the flights exiting the area above 20,000 feet. I am maintaining my easterly heading at 500 to 1,000 feet AGL, in a slight weave with my wingmen in Vee formation. Mike splits his time between the radar scope, visually searching the skies for threats, and checking our geographical egress route. We are cross checking our location by counting the smaller north – south oriented ridges coming off the main East – West ridge. I radio the flight for a fuel check. All 3 of us have good fuel status.

(more…)